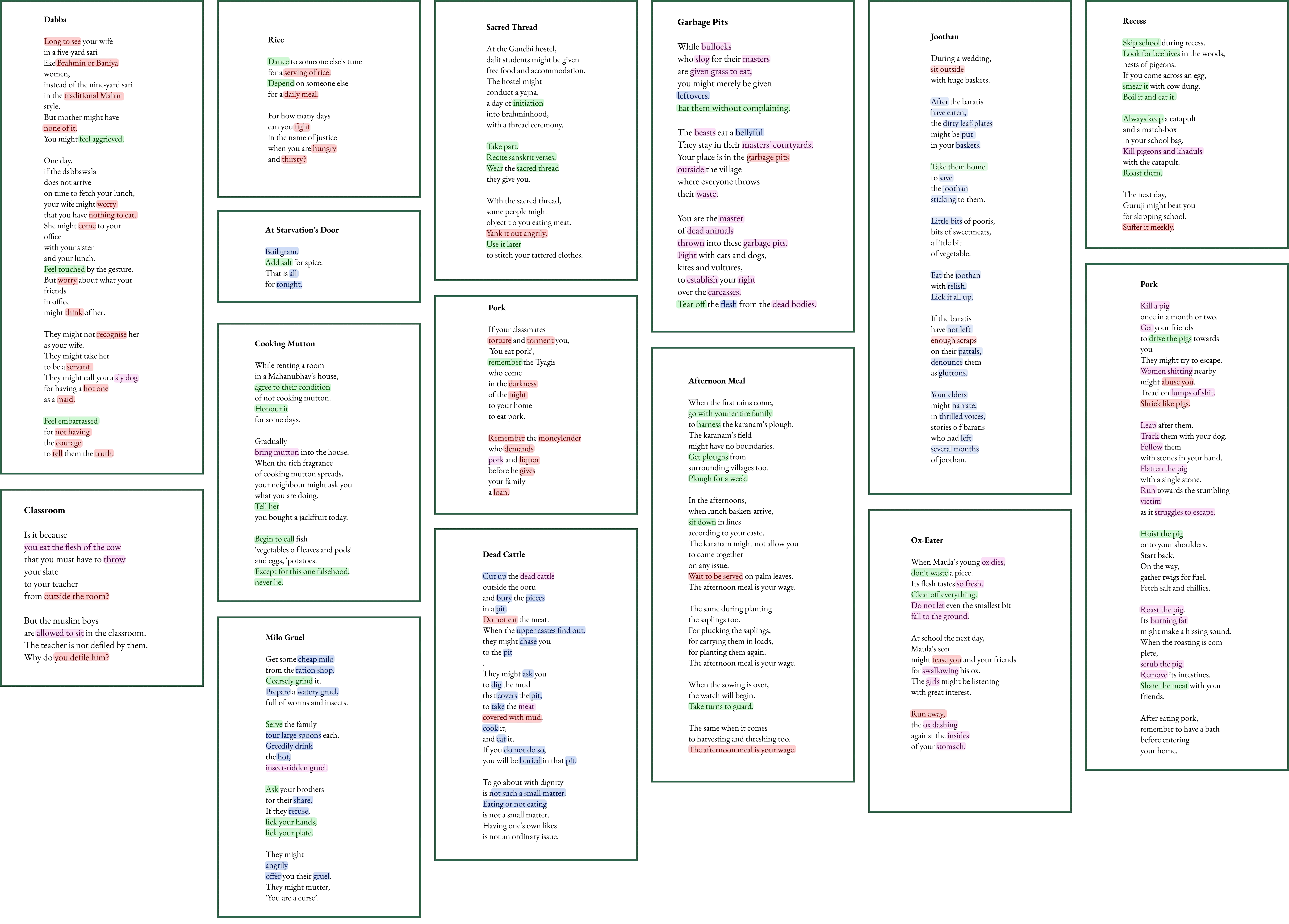

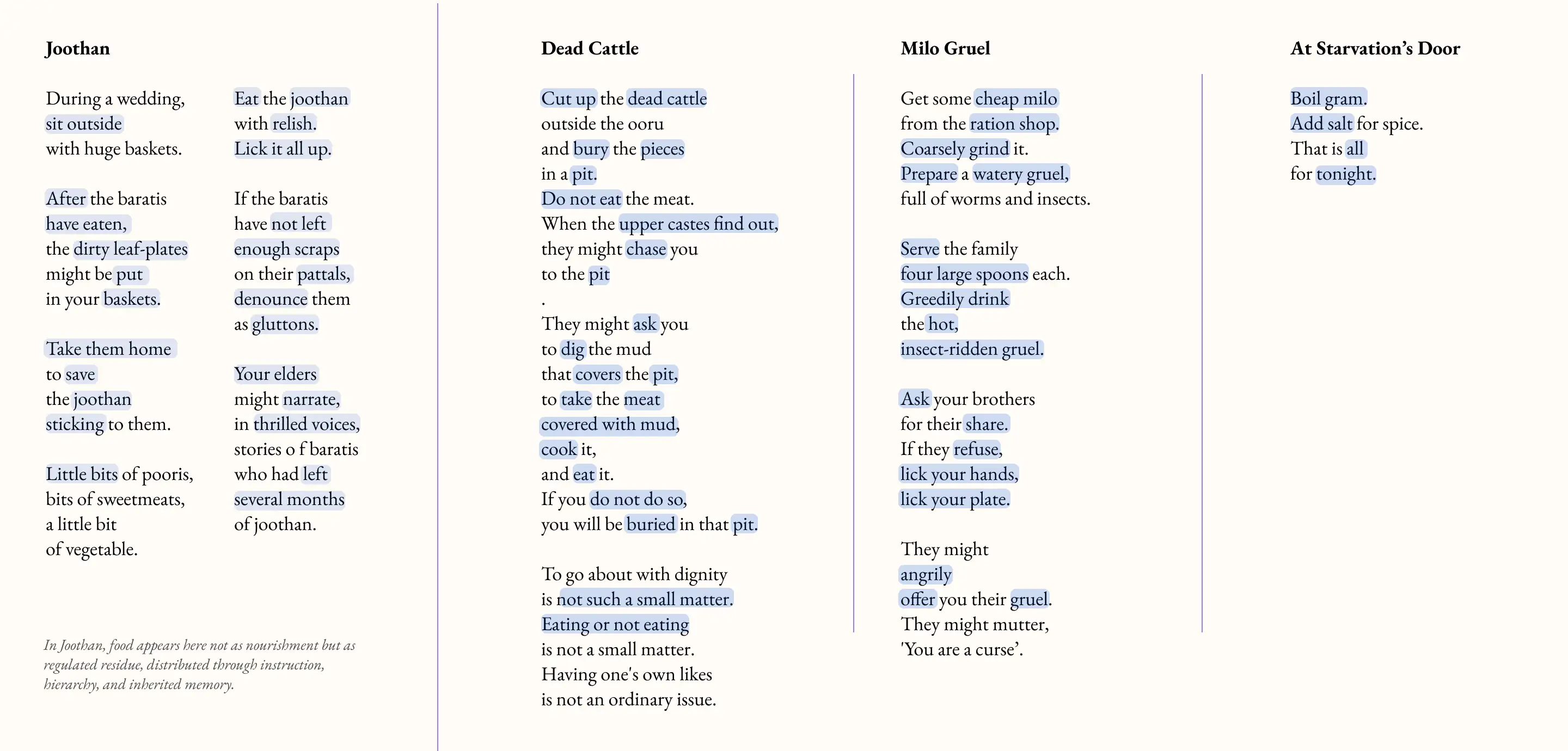

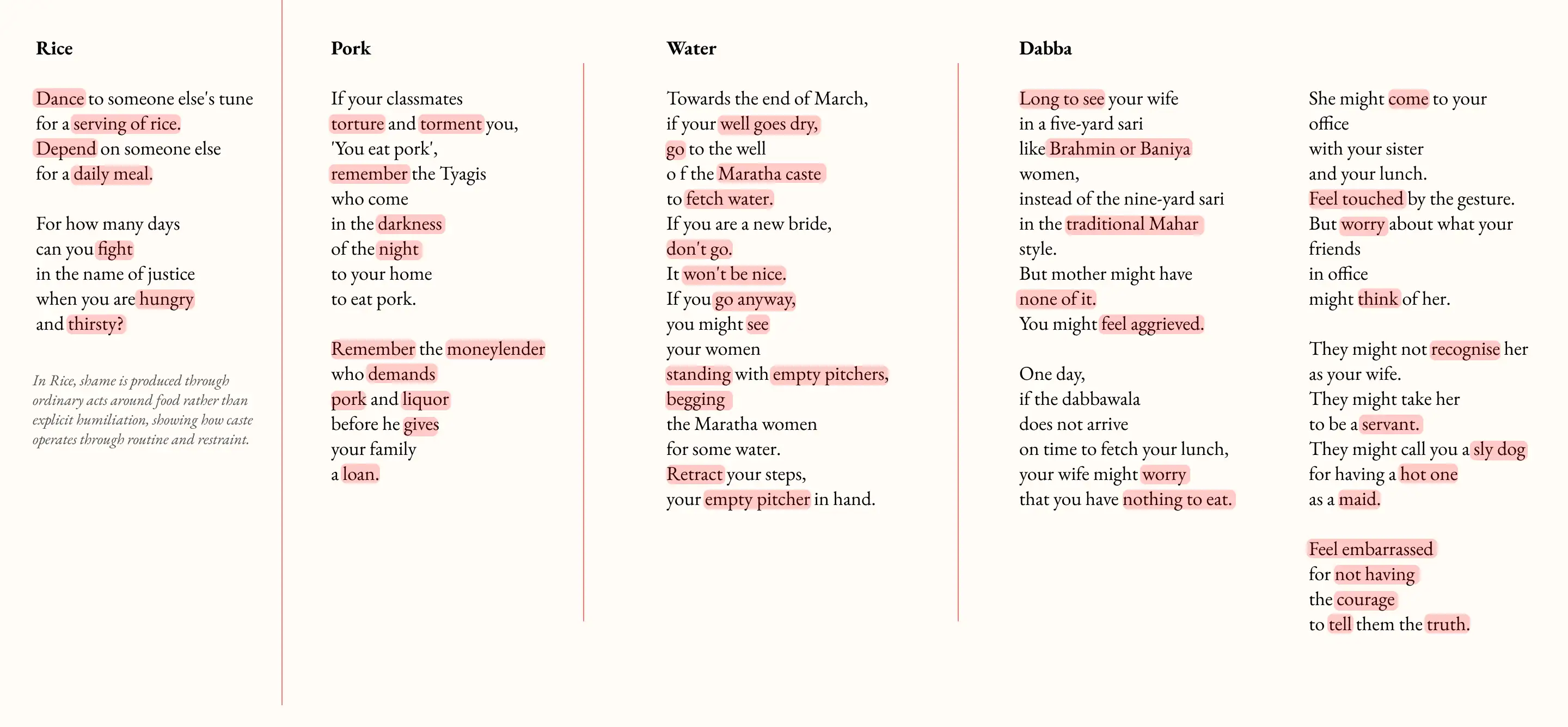

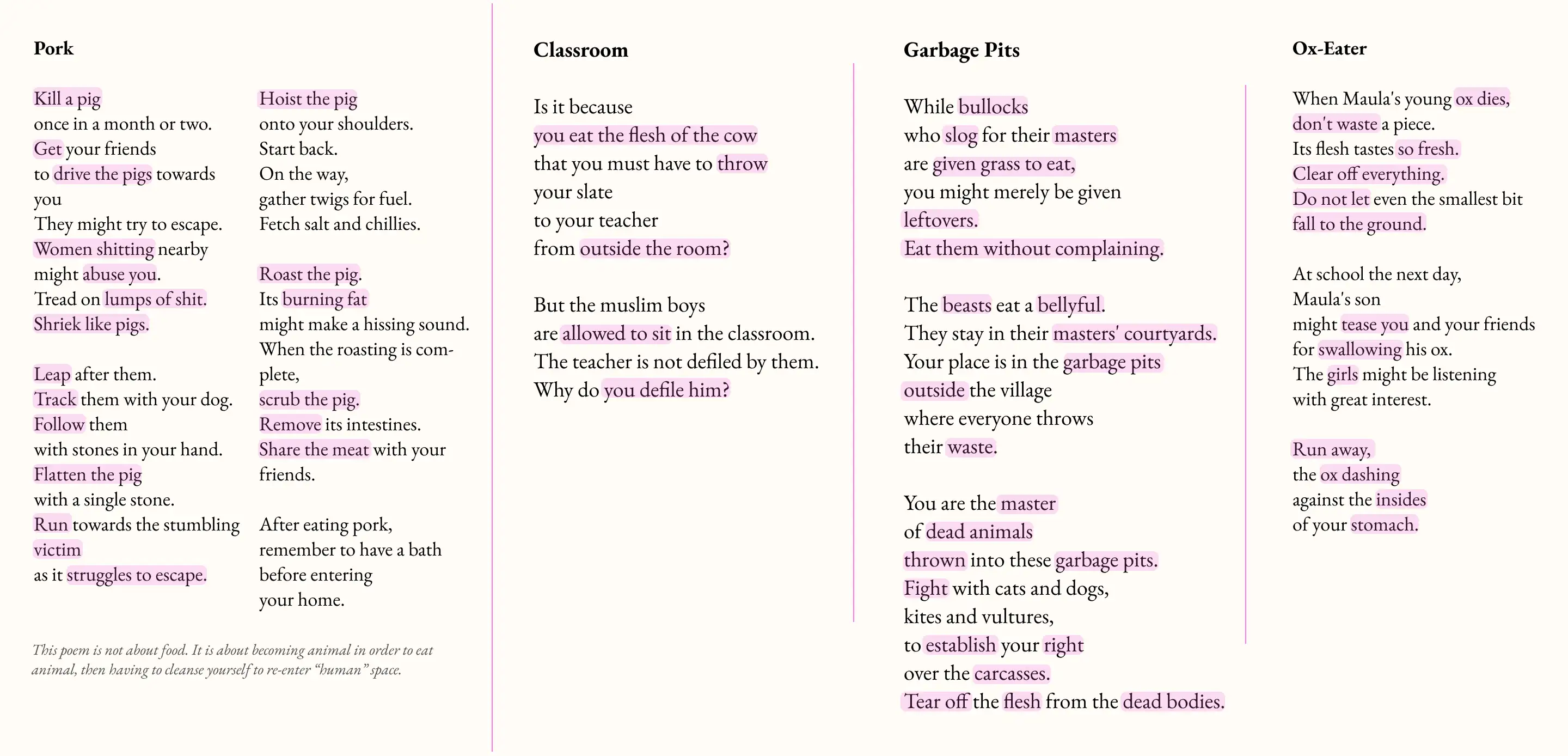

This project emerged from a reading and annotation workshop (Rajyashri Goody’s

Don’t Lick It All Up) that examined a set

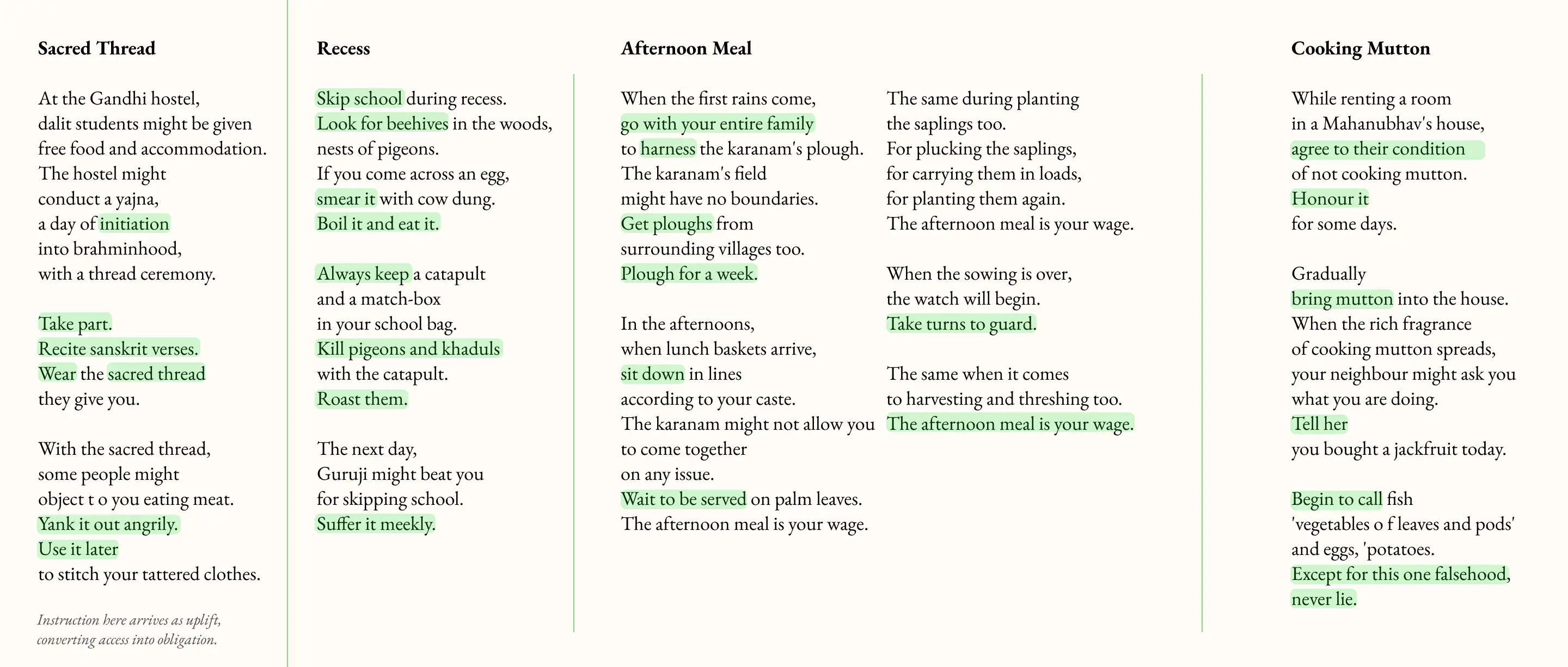

of poems describing everyday acts of eating, labour, schooling,

worship, and survival. The poems are drawn from Dalit writing in

translation.

Dalit people have been treated as untouchable and impure for thousands of years, and many are still denied basic rights to land, food, water, and literacy in India. The initial question was simple: what happens if these poems are read not as individual testimonies, but as systems of repeated commands?

Rather than analyzing imagery or emotion, the workshop focused on tracking instructions and routines communicated through the text. The poems were treated as evidence of social inequity, where violence is normalized through repetition rather than spectacle.

This project builds on top of that exercise. Examination of sixteen of those poems is presented together, followed by a thematic reading that traces how the same structures recur across different contexts. The aim is not interpretation, but visibility. The aim is to improve the visibility.

Dalit people have been treated as untouchable and impure for thousands of years, and many are still denied basic rights to land, food, water, and literacy in India. The initial question was simple: what happens if these poems are read not as individual testimonies, but as systems of repeated commands?

Rather than analyzing imagery or emotion, the workshop focused on tracking instructions and routines communicated through the text. The poems were treated as evidence of social inequity, where violence is normalized through repetition rather than spectacle.

This project builds on top of that exercise. Examination of sixteen of those poems is presented together, followed by a thematic reading that traces how the same structures recur across different contexts. The aim is not interpretation, but visibility. The aim is to improve the visibility.

_P3IO3dfdT9xftbJYrhVp_.webp)